MEMORIES - Jan and Ted van den Driesschen

The following excerpts are from my youngest brother Jan, who put his wartime memories into a book called “Petite histoire”, “Little History”. To make the story more available to a wider group of readers I decided to translate the book in English.

Recently during a conversation with some friends I realized little was known of how Holland suffered during the war years of WWII. I do realize that on the scale of suffering there were and are many more cases of suffering in the world, Holland not being the worst. This brings to mind of course the holocaust, the camps under the Japanese. As countries go the unspeakable suffering of Russia and Poland. Russia lost 10 million people; the country was razed to the ground. The Siege of Stalingrad; the people were cut off for twelve months, unbearable suffering of a harsh winter, faced with constant bombardment, raging battles, starvation to such a degree that people reverted to cannibalism. However in this particular case I like to share these extracts with some of my friends. It gives a realistic insight of the suffering of the Dutch people, especially in the last winter with half of Holland liberated and the other half with freedom so close yet so far.

To give a little of the background; our family consisted of the parents, four daughters, in order of seniority, Dora, Ria, Lice and Joke, three sons of whom I was the eldest, Hennie next and Jan the youngest. Jan was 13 at the time of the hunger winter. Personally I can’t imagine anything worse than to have to starve all the time. Personally I did experience starvation but never to the extent that my brother did and would not have swapped his experience for mine although having been exposed to the heavy and relentless bombing of Berlin in ‘43/’44 I survived in a well fed condition; crawling out of rubble more than once. The Berliners were living rather well and I got the same rations as they did. There were always special rations particularly after a heavy air-raid.

Holland a country of milk and honey could have lasted out the 5 years of war if it had not been plundered bare by the Germans. As you can read in the following story I escaped from Berlin with perfect timing the 6th of June 1944, ‘D’ Day. After staying home for a couple of weeks on my ‘(iI)legal’ leave-pass, I had to disappear. I finished up, with my younger brother Hennie, in a camp for ‘underground’ illegal fellows. We lived with twenty two fellows literally underground in a hole in the ground camouflaged by a cow-shed. We were situated close to the Belgian border. We became involved as partisans when the Allies approached. It was like sitting between two steamrollers, which even became worse when ‘Operation Market Garden’ took place right above our heads. We became involved, among other things, trying to save an American crew of a crashed Glider. In spite of our warnings, they pig headedly refused and naively believed they could just drive off in their jeep, back to base. The Germans gratefully made use of their jeep, leaving the bodies of the Americans upside down in foxholes, alongside two of our fellows who’d undergone the same fate. Of course all this had not gone unnoticed by the Germans, who sent a combat-patrol of platoon strength after us. We bolted all night through paddocks and negotiated numerous fences and creeks to reach the English lines to be free at last. A few days later I found myself in the army with the regiment Stoottroepen. All this to say that I escaped the hunger winter, being rather well-fed; spending a lot of time in the trenches on the River Maas, (Meuse) wondering how much my family would be suffering. After the German capitulation I immediately signed up for the war in the Pacific.

Compared to the suffering of so many people I consider I had a rather charmed life, having survived 9½ years of warfare. Anyone interested enough could read my Berlin chapter. It really was a revelation to me to find out how my brother experienced the Second World War.

The following compilation consists of my brother’s experience and excerpts of the diary of one of his teachers, a monk, which I put in chronological order. Ted van den Driesschen

‘D’ DAY

It’s the little adventurous things that stick more to your mind rather than the facts of a war you do not understand.

War is like a game, like searching a downed plane for instance. The Plexiglas was ideal for sawing and filing to make rings and pendants. The pendants would be mounted with silver ten cent- or twenty five cent pieces.

The most valuable things would have been taken by the ‘Moffen’. Word had it that German downed planes would be given English markings.

One was not allowed near German planes, they would be surrounded by barriers, like at the ‘Ezelsdijk’ near the Eye Clinic.

My eldest brother Theo was put to work in Germany ‘Arbeitseinsatz’. His bed was never empty for long; ‘onderduikers’ (usually young men in hiding, to avoid ‘Arbeitseinsatz’, - enforced employment in war industry-) would come regularly, usually only for a few days. Sometimes they paid either with a loaf of rye-bread or a ticket to a concert.

Father would not allow us to go to the movies (no true patriot would watch German movies!). It’s the forbidden fruit one wants to taste; this is how we saw the film ‘Seven years of Luck’ on the sly. Unfortunately I missed out on ‘Max the wrecking pilot’, by Heinz Rühmann. As well as ‘Die Goldene Stadt’ a film set in Prague.

During our catechism lesson our Chaplain warned us about this film, because of nudity. The warning made little sense as the movie was classified, —above eighteen only—. By courtesy of yet another ‘onderduiker’ we got tickets to a ‘Snip & Snap revue’ in 1944. It was in the Rembrand-theater on the ‘Oude Gracht next to the Augustine Church. I used to sing in the Choir in that church when somehow the demise of the Cathedral Choir, led by Father Otten, came about. I became terribly embarrassed about the short skirts and the bare legs of the Danish Choir-girls. Especially because of father a God-fearing man. “Substituting shame” it would be called later in terms of psychology.

We regularly received letters from Berlin from brother Theo. The letters were adorned with stamps carrying the head of Adolf Hitler. Repeatedly lines were blacked out by the sensor. He was bombed out three times.

I will never forget the sixth of June 1944, for two reasons. First my brother, wearing a Tyroler hat, stood at the front-door. He’d taken a train from Berlin. My sister, the selfsame I had promoted to our maid, did dabble in the underground and persuaded her superior to produce an ‘official’ telegram including Swastika Stamps etc. - “ Father dying, presence urgently required.” - When I answered the wild ringing of the old fashion doorbell, there was my brother asking “Where is father, where is father!” He pushed me aside and stormed upstairs to the parent’s bedroom, where, of course, there was no father, he was at work in the jail at ‘Wolvenplein’.

Brother Theo was not at all impressed. He’d been, in spite of all the bombing, much better off in Berlin. He was home for six weeks; (correction two weeks.) he was not allowed to show himself in front of the windows, lest he be spotted by neighbours, betrayal and the risk of raids. (As a matter of fact Hennie and I had to hide one Sunday under the floor when there was a raid in the street.T.) Meanwhile he finished the neighbours library of ‘realistic’ novels. - ( correction; of the six weeks I spent in Utrecht I was four weeks in hiding at various addresses, one of which was with Mr.& Mrs. Asperslag , down the street. They were a pedantic couple not averse to boasting about his blowing-up of a canal-barge during curfew, when he was incredible lucky; a German officer actually asked Mr. Asperslag for directions. Mr A. then offered to take him there, thus avoiding being checked at all the hastily thrown-up check-points. The reading of ‘realistic novels’ at home was highly unlikely with father in charge; however mrs. Hijkoop, who had the tobacco shop at the corner, gave mother a book on sex education for me to read.. This very book was taken off me by the Asperslag’s as being unsuitable for me to read! I was 21 at the time!)—

· Six weeks later he left on the quite, taking brother Hennie with him, address unknown. Hennie had just finished a College of Graphic-Arts course and was called up for ‘Arbeitsdienst’ (labourforce’)

On the sixth of June we also learned about the Allied invasion in Normandy.

When I opened the door for my brother, it was overcast and a gray day.

I always remember the 6th of June as the day my brother came home and the invasion.

Mad Tuesday:

5 Sept. became later known as ‘Mad Tuesday’, when according to rumours the English had reached Breda and we expected the liberation to be a matter of days. The Germans panicked, so did all the ‘wrong ones’ scampering direction Germany; standing at Central station Utrecht I watched the rush for the trains. 19 Sept. is stamped in my memory as the day for departure to Helenaveen; this happened to be the day of the general railway-strike. In any case ‘the co-incidence’ of that strike, as ordered by our government in London, on the day of my proposed departure for Helenaveen accounted for the fact that I never arrived there. Hence I never did become a priest, pastor or missionary.

MARKET GARDEN

17 September 1944 we watched hundreds of planes flying over. I’m standing at the same spot between ‘Tuinwijk and Tuindorp where 2 years ago the Germans, just arrived from Russia, had stood-up their rifles in stacks of four. By word of mouth the news spread: British paratroops landed near Arnheim!

*********************************

From the diary of brother Chromatius:

19 Sept. According to rumours over the last few days, Utrecht had been declared an open city. This does not tally with what I saw during a walk today.

Bridges covering tank-ditches demolished, on ‘Antoniedijk’ traffic blocked by ‘Spaanse ruiters’ (barricades). Eindhoven captured by the Allies!

20 Sept. Tremendous activity in the air. Again airborne landings. The joy over Eindhoven somewhat dampened by the bombardment.

24 DEC. Yesterday we had to make do without a fire, because the blasted thing had to be decapitated to be fitted with a new grate. We were horrified at first at the enormous amount of fuel it burned up, considering the limited amount of fuel we had and the duration of the winter.

There is a marked improvement our refectory (including study, kitchen, recreation-hall and prayer-room) is warm again. Considering the turnaround of the weather, the harsh cold wind temperature eight ° below zero, this is absolutely essential. This change also brought about a clear sky which meant the resumption of the bombing of the area around the town. However this is not the central point of focus, where people are more occupied with the bitter misery of hunger and the biting cold. The suffering of Mary and Joseph —now 1944 years ago— repeats itself in this town indeed the whole of the country in thousands upon thousands of families. Our people wander around with empty stomachs; many in threadbare rags. Right now children are also born in cold houses by the light of a small oil-light or a stump of a candle. They also are wrapped in threadbare rags.

We not only remember the event of Christmas we relive it! But for many the devotion is lacking. My heart bleeds when I think of the many wretched souls totally dependent on the central kitchens. Who could survive on half a liter of distasteful dishwater that’s supposed to be soup, supplemented by a weekly ration of 800 grams of bread? — (The so-called bread not only looked but tasted like sawdust that had been kneaded into 10cm. square loaves T.) — Of course assuming there was no hitch with the supply. What are parents to do when their children cry for hunger? The area that has been stripped and exhausted through bartering and begging keeps growing larger. People, pushing heavy handcarts, walk as far as Zwolle and surroundings — (about 100km as the crow flies, in their search for food T.)— These are appalling trials most people do not recover from.

Added to that the consternation caused by posters everywhere: “All men between 16 and 40 years shall be recruited for the German ‘labour-process’. Call-up will follow. Anyone providing shelter to ‘onderduikers’ — (people going underground, to avoid recruitmen T.)— will have all their worldly goods and possessions confiscated.”

With all that our railway men’s strike has been in vain, No Englishman crosses the Rhine and the Germans advance in Luxemburg and Malmedy. The sorrow among our people is beyond description and worsens by the day.

The Night-mass will take place at a.m. by the light of ten kerosene lights. Bro. Cornelio and bro. Bernulfo will remain on guard duty at home. It’s too dangerous to leave a house alone these days. The rise in poverty brings about a rise in crime and we don’t fancy finding a home stripped after the night-mass.

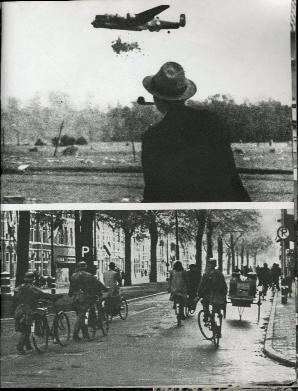

Left photo - The Hunger Winter

Left photo - The Hunger Winter

Right = note the solid tyres on the bike, no pneumatic tyres left!

25 DEC. Our indestructible optimist bro. Cornelio, who persistently maintained he would celebrate his father’s birthday in Tilburg, has ultimately admitted defeat. It was a bitter pill to swallow.

Twenty fifth of December! The drone of the bombers, the barking of anti-aircraft fire and the howling of the sirens have come today to remind us of the “Peace on Earth”. After all we are Christians?

27 DEC. It is eleven degrees below this morning. Creeks and ponds are frozen over. Hopefully they can keep the rivers and canals open, our only line of supply by barge. Thousands of people would face death by starvation if the supply of grain and vegetables stops for a few weeks. The only possibility, get your own supply! Oh, this own supply! Hunger forces people to long treks. There they learn about despair and hopelessness when they have covered 100 km. without any result. I know someone who armed with brand-new shoes, methylated spirits and sugar for bartering, (enough to conquer the world!), came home empty-handed after spending a whole day‘s pilgrimage, except for a pound of peas, which he .... stole!

Only chance to obtain anything one has to go to Overijssel. However no man between 17 & 40 years will get across the IJssel-Bridge and if you try the alternate route through Amersfoort you’ll be immediately put to work...... (on German defense works T.)

25 JAN.

It’s official, by word of mouth from the most prominent people; we’ve been informed that our liberation is close, very close and more of such fine things.

But the Western front is stagnant and we have to endure yet another harsh winter with as much hardship as the explorers who had to stay the winter at Nova Zembla. All the musea (museums) for clothes and theatre-costumes have been stripped by the Germans. The people fortunate enough to posses blinds had to surrender them to the Germans. They were ‘allowed’ to personally come and deliver them. It was said that the material was utilized for the manufacture of camouflage-jackets.

In all his misery and suffering brother Theoduul provided us with an interesting experience, which had its humoristic aspect. For days he suffered; first with a severe mysterious toothache, where after he developed a nasty infection under his right shoulder blade. It developed into a large swelling, a real carbuncle that kept on thriving, soaring up his temperature making his life unbearable. Our private nurse, brother Norbert could no longer cope with it; the patient had to stay in bed, which meant in a cold unheated room; his temperature went up to 39°; the doctor couldn’t make it; the patient was in absolute agony; the direction was worried; they took steps and decided one of the brother-nurses had to vacate his room in the hospital; as all beds were occupied and there was a long waiting list, (what’s new? T.).

There was one more problem, transport. How to get a patient to hospital in the current situation? One sees them transported on improvised sleighs, or the baker’s cart, without anyone raising an eyebrow. They carry children on stretchers, also adults provided the distance is not too great; but what to do with brother Theoduul the heaviest built in the house and in spite of the war still quite hefty.

Luckily in school there was a large ancient stretcher for use by the air-wardens. It suited the purpose well but the usual canopy was missing so the patient was exposed for God and all to see. Soon the monstrosity, set on high wheels, stood in readiness in front of the house; our colleague on it wrapped in blankets a sheet over his head, the show ready to start. It was heavy work for the four of us to push the cumbersome vehicle through the snow. Two up front and two behind. They tried desperately to maintain a suitable expression on their faces in order not to burst out laughing. Even the patient forgot his pain. To top it all off, people along the way watched with sad, oh so sad expressions on their faces, some women taking out hankies to wipe the odd tear away; declaring never to have seen such a sad scene. Kids stopped playing and stood like statues; even German soldiers looked on with sympathetic expressions at the stirring sight of four black brothers struggling to take their dying colleague to hospital.

This trip of brother Theoduul should forever remain as a tragic-comedy in the annals of the congregation.

29 DEC. Clear day, light frost; there is skating activity on creeks and ponds. Whoever has got an eye for it can admire the clear crisp landscape and enjoy the romance of silver moonbeams; however who listens to the people realizes the stark contrast between appearance and the reality of our life.... This afternoon Hilversum and Bilthoven were heavily bombed.

31 DEC. Half past twelve this afternoon we learned about a Mr. Van Dijk’s proposed trip to Zwolle with his truck. He was prepared to pick up a load for us, provided our colleagues over there could arrange some supply for us. This meant they would have to be notified soon in order to be prepared for the truck’s arrival on Tuesday. Someone has to go post-haste to Zwolle. As I am from Zwolle originally I was the chosen one. Saying good-bye to Brother Superior, wishing him a blissful end of the year I took off at half past two. I’m no speedster nor have a great deal of endurance; I decided to keep up a steady speed and make it to Harderwijk the first day. The weather was not particularly bad only a strong headwind I therefore had decided to leave my hat at home, I hate to have to hold on to my hat to guard against gusty winds. In a good frame of mind I carried on, despite a few spells of snow; on past the rural ‘De Bilt’ where I was greeted by tolling church-bells, on past the bare woods and lines of trees near ‘Soesterberg’; then pushing up the ‘Amersfoort’ hill, then bumping along the bad back-road near ‘Hoevelaken’.

At ‘Nijkerk’ dusk set in; there were crowds of people returning from the New Years Eve service in Church. It was already dark when I reached ‘Putten’;

I was unable to see the damaged township. Pushing the pedals became heavy; there was something wrong with the bike, being dark and having left my torch at home, I was unable to find the trouble. About seven o’clock I reached ‘Harderwijk’. After being shown the way to the presbytery, I was welcomed by the Parish priest as a long awaited guest. This was where I celebrated New Year instead of the usual way with my family ‘Tilburg’.....

15 JAN...... Today a kitchen was established in our school for the children. Three times daily 50 children.

would be provided with a warm meal; that meant 900 children took a turn. This was initiated by our parish priest with with cooperation of the Municipality. The arrangement is interdenominational.

16 JAN..... This disaster-stricken City is threatened by diphtheria and other contagious diseases, usually caused by bad- or under-nourishment.

Many houses show warnings stuck to the front door and even though some have been put there in order to avoid raids or searching of the house, many are genuine to even further exacerbate the misery. There is a family in our parish, where all six children are down with diphtheria, the mother can hardly walk because of open sores on her legs and the father has a serious stomach ailment. Who can help those people? Who can ease their immense burden?

A charitable hand can offer here and there help to fill a need, but it can not solve the problem on the whole.

20 JAN..... Last night a thick pack of dry snow covered the world. Virtually all morning the flakes came floating down. Frost set in at nighttime it looks like we won’t get rid of this troublesome cover in a hurry.

The press predicts the food-calamity will get worse over the next few weeks. Haven’t we reached the pinnacle already? This will mean the downfall of many families, who used to live comfortably before the war. The prewar poor are at present not always bad off, getting by through black marketing and other sinister practices; -( I’m afraid I don’t agree with the latter! A rather poor observation from an educated man. T.) - But pity the people without connections and anything to barter with, who have to get bye on a normal salary. (Like our parents J.D.)

Our school experiences difficulties with the feeding of the children, upset parents whose children have missed out and worse still, part of the available milk-powder appeared to have been stolen this morning. A move has been started to evacuate children to parts of the country where there’s still food to be had. The biggest problem is transport. Next week a group will be moved to ‘Overijssel’ by ..... a garbage truck. .....

26 JAN..... Meanwhile the bread ration has been reduced to 500 gram’s per person per week and we have been “consoled” with the message that the supply of potatoes also will be reduced. Since all the roads are blocked due to frost. East and West Holland remain separated, they allow potatoes through; the rest is confiscated even though the wretched things have covered hundreds of kilometers, on foot, on dilapidated push-bikes or handcarts of any description over snowed-under slippery roads, in the bitter, bitter cold.

Have we reached the ultimate of misery?

27 JAN. Exhaustion is taking too long; death is all around. Daily one hears of victims dying either for cold or starvation. To understand the extent of the calamity one has to observe the passion and intensity which people beg with, just for a peace of bread. To meet a good friend who looks emaciated beyond recognition makes you realize the height of the tragedy we’ve reached.

28 JAN.

It was announced from all the pulpits. A request from the committee of the hospital for people to take in a child under the age of one and care for it as many mothers were no longer able to provide their children with sufficient warmth due to the lack of fuel. Something which already had claimed many victims. The temperature remains bitter and roads are impassable. There already are many victims between Amersfoort and Zwolle. The emaciated wretches struggle till the death against exhaustion and cold. Someone from the van Humboldstraat returned from Zwolle with a decent booty. She was dead two hours later. Similar stories happen to be a daily occurrence.

We learned from our colleagues in Joannes de Deo hospital that the food situation in the hospitals is just as bad. Patients in the Academic hospital had been fasting all day; they got something to eat at night time.

Brother Theoduul had his operation last night. He got rid of his furuncle, his temperature dropped and he feels much better.

2 FEB. Whist we unloaded our freight (Food supply from ‘Zwolle’ brought about by the efforts of bro.Chromatius, J.D.) the sky in the South/West was lit-up for a long time. From the direction of ‘Jutfaas’ ships carrying oil-supplies had caught fire. (Bombed?) This illumination did not care about black-out regulations and lasted for hours.

10 FEB. Saturday. The end of the worst week we ever experienced. Words fail to describe the catastrophe that has befallen our people.

There is nothing, but nothing. Since the frost transport has still not recovered. Did the reluctance of the weather play a role? I don’t know. Some of the boats appear to have been confiscated. What was available on our coupons this week?

NOTHING!!!!!

No bread for the starved, no potatoes for the emaciated. The only available ration, sugar beets. Who can live a whole week on sugar beets? How did our people survive this gruesome week? We knew about the potato-peels and the tulip-bulbs. What else did one eat in those ravenous conditions? The whole week there was nothing to be had from the bakeries. The ovens were not lit. The word hopeless is heard more than ever. Everything is hopeless. Subject of every conversation the hopelessness of the food situation. How many wasted bodies suffered irreparable damage? How many did get a visit from the grim reaper to claim his victim or start his chronic work? Was it coincidence there were daily requiem services? Bodies remained for days above the earth afterwards. Waiting time for coffins, about eight days.

The hunt for food on the way to the river ‘IJssel has dropped off. Why? Whoever, weak for hunger, realizes the futility, he who has experienced the confiscation of his food at the bridge, will not try again, he who slept in a hayloft by 12 below zero, lacks the courage, he who’s feet still have open sores from the last journey, he who negotiated the snowy, slippery roads, lacks the courage, he like the woman across the road, cried all the way from Utrecht to Ommen and from Ommen to Utrecht, rather dies at home, than to try again. The stream of exhausted women, aged men, and pale girls, unescorted school-kids is slowing down One stays home, defeated, starving and extremely bitter.

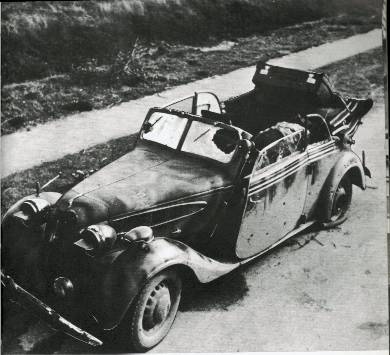

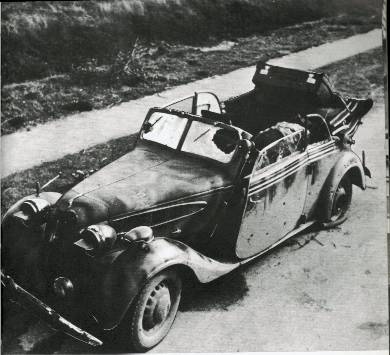

On the 6th of March 1945 the Dutch Underground was in dire

need of a car, they ambushed this one. By sheer coincidence

one of the passengers was SS General Rauter. In the ensuing

battle, he was heavily wounded. As a reprisal 117 hostages

were shot by the Germans on the very same spot.

Evacuation for children is in full swing. The organization takes in every suburb and every family. The greatest problem is Transport. Everyone who still has a truck for one reason or other is prepared to help, but there are not enough and a multitude of obstacles. Thousands of parent long to get their children across the river IJssel. Although they would have preferred to stay together on account of the dangers of war, staying together would certainly mean death. This week three wooden gates were stolen in our neighbour-hood. What one does for firewood! At dusk we spotted a few suspicious characters behind our house, for security we’ve mounted a bell on the backdoor....

******************************************************************************

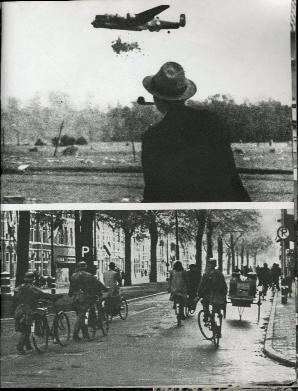

In the last days of the war the RAF opened their bomb doors for food instead of bombs. Underneath: whilst the conquerors are in retreat and the Dutch already hung-out the flags to celebrate.

My brother Jan. (13 years old at the time.)

My brother Jan. (13 years old at the time.)

SALT OF THE EARTH:

It’s March; I’m sitting on the wall of a little bridge in the country staring in the distance to where I suspect the beginning of spring. The willows are budding; nature has been to the barber. The sun pricks somewhat hesitantly through the mist. A pair of grebes dives simultaneous. The water under the bridge is never the same. A straw disappears in the sun. A helicopter flies low over the pale grass. Somewhere near a military exercise. — Forty years ago two Mustangs razed the tops of the trees. I smell the timber and the earth of the Seypestijn Bush. I chop tear and gather wood, packing twigs and young branches hurriedly in a packing case mounted on wheels, that’s been to ‘Indië’ and back with less effort than it takes me to get the wood. I feel beat and exhausted as I’m pushing the load. I find the necessary energy a moment later when overtaken by a horse-drawn dray. Unbeknown to the driver I hook the cart with a rope to the dray, utilizing the horsepower, which takes me past Verheul de toll-keeper. At the sign ‘Achtung Baustelle’ I have to unhook.

At the railway crossing stands an anti-aircraft gun, an armoured shield mounted with several barrels. Hanging around are a few ‘Moffen’ maybe two years older than I, although much better nourished than I. At home we are out of salt. Arnheim failed and Borculo (where the salt comes from T.) fails to deliver. Where do we go from there when there’s no more salt!

SKATING

No generation has skated more than ours. The big monster in class, we sometimes put rubber bands on top of it, devours coal and soon the coal-bin empties. Next we have a coal-holiday! Nevertheless they give us plenty of homework to take. Long winded problems like.... “One lowers a brick of x amount of dimensions in an aquarium of x- amount dimensions.... the aquarium holds x-amount of liters water .... Question: How many goldfish are swimming in the aquarium?” Or: “A leaves from point B at twelve noon and C leaves from point C at half past twelve, what time will they meet in point E?”

At the ice-rink ‘Siberia’ near ‘Willem van Abcoude Plein’, the brothers spun around the inner-track reserved for figure-skating. It was a sight those swirling skirts of their togas. I was too young for plus-fours, a.k.a. ‘turt-catchers’, not to mention long trousers. That’s how you skated in 12 - 16 degrees frost in shorts with knee’s like the pigs trotters you missed in your pea-soup. Your choice of skates was out of a big heap of ladies skates for figure skating, with bindings and leather heel pieces, which hadn’t been sharpened since World War I. The other choice was the straight types for distance or racing they were provided with straps that had to be continually re-fastened lest they finished up flapping alongside your shoes and you found yourself skating with your shoes instead. That was the stuff we had to learn with. More often than not we had no money for the ice-rink thus we went into the polder to ‘the Gagelfort Blauwkapel’ near Verheul. You had to work your way trough the snow imagining yourself to be on the East-front, like the photos in the ‘Katholieke Illustratie’. You would not be game to admit to anyone how you felt like a hero with your black alpino cap like a tank beret. My gray overcoat looked somewhat like an army overcoat. You put on a grim face like the ‘Moffen’. On the playground you played Eastern front, two parties storming forward getting stuck into each other fighting a heroic battle till the school-bell went and one had to toe the chalk line to enter school in columns. Mother was not at all pleased with all the holidays we were getting, ice-holidays, coal-holidays, (no heating for the school). At home the washing hung in front of the pot-belly fire. At nights the ice-rink closed with the speakers blaring “Good Night Liebling, Frau wird für dich wachen. Our happiness will come.” The happiness of Liberation?

Without a doubt I was present as an altar-boy at that “Night”-mass. (The mass referred to by brother Chromatius T.) All the lead light windows were blacked-out at nights; the shutters would be removed through the day. There being no electricity the place was sparsely lit by yellow candles. It was extremely icy cold. The only warmth to be had was from your cassock and surplice. A situation which would have been quite normal in the middle ages. In spite thereof one felt joy at the birth of light under the darkest circumstances. All the while one was ravenously hungry. New Years morning after the High Mass we saw a surprising scene, Americans flying high overhead and Germans flying low underneath, ignoring each other completely. Germans we had not seen in the air for months. They were involved in the final effort of the Ardennen-attack to drive the Allies back. —

(These were the same planes which interrupted my breakfast, after a night in the trenches. They did some low-level strafing on our lines, our company downed two Messerschmidts. T.) —

The ‘German Priest’ meanwhile must have disappeared; he no longer lingers in my memory or in my story. (The German priest, who was conscripted in the German army, held the rank of officer. He was in hiding in the presbytery of the parish. T.)

On the other side of the river IJssel.

I must have been early February ’45 when I decided I could not take it any longer, I reached the limit; I reached the end of my endurance.

Occasionally we went to school to go and get a vitamin ‘C’ pill or collect an orange, courtesy of the Spanish Red Cross, and the odd time a plate of porridge served at your school-desk. Afterwards one went home again. Once a week I would join the Signal-box operator’s family Kloosterman, for a meal. Christmas-Eve I rode a bike without tyres along the river Vecht on a mission to try to obtain some milk. I lost a piece of a front tooth in the process when I rode into a foxhole alongside the road and smashed my face on the road deck. The Christmas-trip resulted in half a liter of milk.

Everyday I queued up for the central kitchen to collect our ration of half a liter water soup or indefinable mash. This is where my heartfelt dislike of queues dates from.

I learned from father Collet there were children-transports going east. These transports were organized by Pastor van Nuenen from the ‘Augustin’ church at the ‘Oude Gracht’. We waited in vain for transport, a truck from the firm ‘Douwe Egberts’, until late into the night. Back home they were none too pleased. They were in the middle of eating potatoes with bacon when I arrived, this meant of course smaller portions for everyone. Next night it started all over again assemble at the ‘Oude Gracht’ this time with more success. In the excitement of leaving I forgot to wave good bye to my two year older sister, Joke.

The reason for traveling at nights was; that every moving thing on the roads was exposed to trigger-happy fighter pilots. (Brother Hennie can testify to that and he was not even traveling by road but walking in the field in blue overalls, (the typical dress for partisans!) A German friend of ours told us about her experience as a young girl, when German people walking through town, including women pushing prams were fired on by fighter pilots! T.)

Arriving at the bridge across the River IJssel the ‘Moffen’ (German guards) stopped us and checked the load. Not long after the bridge was closed to all civilian traffic. Arriving in Deventer we were housed by the ‘Organisation Todt’. — (A Para military Nazi construction organization, which was involved in civil engineering and construction of defense- and infrastructure projects. T.)—

We were bedded down on straw in cellars, awaiting further transport. Out in the street I discovered a queue of people lined up at a central kitchen. Half liter portions of ‘Sauerkraut’ were dished out, to be eaten inside. Three times I lined up. Back ‘home’ in the cellars I was fed once more. With my poor luggage I had a new pair of ‘paper‘shoes. In order to save them I walked on wooden clogs.

After endless hassling at the Distribution Office mum managed to get a coupon to buy a new pair of shoes and it then still remained to be seen whether the shop would have a pair available. We succeeded at a shop at the ‘Bemuurde Weert’. I only wore them a few times before our luggage was loaded in Deventer, on a country-dray. I specifically asked the coachman to take good care of my new shoes. He did this very well! I never saw them again!

From Deventer, we traveled, again by night, as mentioned before because of the risk of Allied planes, via, Holten, Rijssen, Markelo, Goor to Almelo.

At Holten we were fed on sour hotchpotch. We spent the rest of the trip throwing-up. I can’t recall how we got from Almelo to Weerselo.

Upon arrival I was among a number of boys lined-up, according to height, on a podium in the community-hall. Since I was the smallest I was the last to be selected. It was like a slave market, the farmers called out their preference in turn, first in the pecking order of course were the Gentleman-farmers: Lohuis, Kamphuis or whatever they were called. I was allocated to the “Olle Schiller”. Jan Kuipers took me home on the back of his push bike. It was a hovel; the roof nearly touched the ground. The floors, except the red-tiled kitchen, consisted of compacted earth. The stable, housing four cows adjoined the live-in kitchen. That was about it. Outside there was a real well the only source for water. I was to sleep in a small room connected to the stable, where there also was a sort wooden box with A straw mattress, where Gait slept. I had to sleep next to him. Gait would step out of his clogs and take off his work-jacket and keep his trousers on to go to bed. The only one I have not mentioned yet is “Marie”, their unmarried sister. The condition of the live-in kitchen was incredibly dirty. The soiled and stained walls were covered with portraits, paper-cutouts and fly-shit.

Jan was the eldest of the three, a simple farmer who would look at you with trusting bright blue eyes. A pure soul, innocent almost simple minded.

Gait was the intellectual; he had been to the gymnasium (grammar-school) at Oldenzaal; He’d been employed as the town clerk of Tubbergen.

Now he just sort of bustled around at the pigpen. Gait was incredibly lazy and dirty. According to Annie’s mother, the sister in law of the “Olle Schillers”; she lived in the house next on the ‘Oldenzaalse’ street; Gait once burnt his leg, consequently they had to take off his black sock, to reveal a leg that did not differ in colour from the sock. Just prior to the war Gait had been requested by the Council to return to set up the distribution system.,br>

I assumed because he was lazy he philosophically resigned himself to simple farm work. Later I learned he died of a heart disease and this may have been the reason for his early retirement. Gait was always last in bed and kept on asking me about life in the west, whilst he constantly kept on scratching his near bold head. He sometimes used his pipe with homegrown tobacco to scratch.

I got used to a lot of ‘Fremdenverkehr’—(‘traffic from outsiders. T.)— in the hovel. It was a transit house for the underground illegals, who gathered here to be guided at night to other destinations. One night the kitchen was filled with Germans, sitting on the floor leaning against the walls. They were dressed in blue overalls underneath which they wore their military uniform. They carried pistols which, they said, they would not hesitate to use when caught, for the death penalty would follow automatically.

During the day there was a lively trade with members of the ‘Wehrmacht’ and the ‘Luftwaffe’. Trading anything from eggs to pigs.

Nighttime was used to help people who were not to be seen during the day.,br>

One day an underground character appeared who did not move on but remained until shortly before the end of the war. He unlike the Dutch had a habit of washing himself. Stripped to the waist he would stand at the well and vigorously scrub himself. Immediately afterwards he dragged me out to give me the same treatment. I already was well on the way to join the members of the ‘Olle Schillers” in their habits of hygiene. I only had one set of underwear; I must have been on the nose like the pigs whom by the way were better housed than we, in a new modern stable.

Strange that I, after that many years, can’t recall the name of that man who treated me as a father. For convenience sake I’ll call him ‘Anton’. He took me wherever he went. Except when Germans drove by. He behaved like any Dutch man. Well, Dutch man?! He spoke the language of the district. — (The district includes an area both sides of the border. One could travel an hour either side of the border and the language still sounded the same. T.) —

Whenever a German dispatch rider approached he would quickly yet unobtrusively disappear.

Sundays he would occasionally go out by himself. He would borrow my glasses which I thought looked rather comical. He wasn’t very talkative but I was used to that from my father. During the last stage of the war more and more shootings occurred at whatever moved on the road. We are standing on the land then a couple of English fighter planes streak at low altitude over us. We watch them pulling up as suddenly rattatata..... a stream of tracers, from the tail coming our way. “Take cover” yells Anton and drags me into a ditch. A stream of bullets razes our backs. I could clearly see four cows in the paddock running like mad around in circles. Two oil-barges in the canal were hit. One of the skippers jumped in the water in the nick of time before his cabin was peppered with bullets. Whenever I hear a bang I shrink a few centimeters. Even today when I hear the whine of a yet I sometimes shudder.

Liberation:

We were liberated on the second of April, Easter Monday. Easter had been a drizzly day. The ‘moffen’ retreated along the road past our little farmhouse. I watched them from the little stable-window; one fired a bullet, piercing a neat hole through the glass, narrowly missing my head! A group of parachutists were engaged in a loud conversation, about their encounter with English tanks in Normandy. They talked about how some of their mates in foxholes had been ground to pulp by the tanks.

They threw their rifles and ammunition from the bridge in the canal. At Annie’s they stole a cart to load up their luggage. They also helped themselves to the chickens. That Easter Sunday I ate eight eggs.

Easter Monday, 2 April 1945.... An armored vehicle with a white star stops in front of the farm. I race outside and look through a slot of the scout-car right in the face of the driver wearing a black beret. I said ‘good morning’ and climb right away on top of the vehicle and we proceed slowly to the bridge.

This time there is no father to drag me off the vehicle. — (Our father once, in a rage, dragged Jan off a scout-car of the invading Germans. T.) — The ‘moffen’ at the bridge surrender immediately without resistance. The bridge is lowered.

Whilst lying alongside of a bren-gunner, at the crossroads Fleringen, I have my first practice in English conversation, the subject being my sisters, of course. There are still retreating Germans to be expected. The SS are still fighting a hard battle in the Twicker forest near Hengelo. For hours we can hear the chatter of the machine guns.

Next day I bartered with the Canadians near the canal, where they were hosing down their coal trucks. Sunlight soap, Cadbury chocolate, cigarettes for eggs. Some of the Canadians spoke French, one even spoke Dutch, he migrated to Canada before the war. Through these soldiers we learned of President Roosevelt’s death.

With horse and cart, the eldest of the three brothers, Jan and I traveled to Oldenzaal to visit Jan’s family. (By the way the horse was the same one that bolted, with me on its back, when a V1 prematurely landed and exploded nearby.) Oldenzaal was crowded with tanks, surrounded by youths begging for chocolates and cigarettes, for papa, mama and the whole family. Shortly afterwards a disaster took place on the market. Some of the young people had filled a Jerry-can with cartridges and explosives and by way of fireworks lit it. Among the dead were an English officer and several wounded.

I also could be blamed when I found a ‘panzerfaust’ — (a type of Bazooka. T.)— and hid it on the farm. Just as well I did remove the detonator. This also could have finished up in disaster.

The total surrender of the Germans came over the loudspeakers in the village where since the liberation we went every day to listen to the news. The date was the eighth of May.

***********************************************************

April 1984:

I find myself behind the former convent in the ‘Deken Roe’ street at my friend’s place. His garden borders the convent. Here I took Latin from the moderator, because the railway strike prevented me from going to Seminar in Sept. ‘44. The Latin textbook started with anno,amas,amat.

In a state of celibacy these words are of little use. — -This is where in the summer of ’43 a British bomber crashed nearby. From our house we observed it coming over, burning like a torch. One crew-member crashed through the roof into a bed of a person living in Kapel street, stone dead. - —

An hour after the visit to my friend I find myself in the ‘Van de Monde’ street in front of our previous home. Our front room has been converted into a garage in which the pastry cook’s Morris just fits. By chance, the baker (retired) and his wife arrived. — (The pastry-cook, our next door neighbour, bought our house after our parents moved out. T.) — Moments later I’m in the erstwhile living room of my parents, who passed away in the seventies. My hands stroke the marble of the fireplace in the back room.

Here I sought some miserable warmth from the little emergency stove. During the hunger winter we tried to read by the light of a little oil-lamp or alternately we peddled the old treadle-sewing machine with a bicycle-dynamo attached. This soon exhausts. So off to bed. I stole out of the kitchen, from our own rations, until there was nothing left to steal and I left for Overijssel. The ration consisted of two slices of coarse bread and half a liter watery soup from the central kitchen. Marble survived it all, stays cold like a headstone. On the fireplace shelf was a small radio which we did not surrender, — (By order all radios had to be handed in to authorities, so people could not listen to Radio London. T..) —

We often listened to Radio Beromünster (a Swiss Station T.) their German didn’t cause as much suspicion. I can still clearly recall the Swiss accent.

I could also listen to the messages from the East front and a ‘Wünschconzert’ (program for requests from German soldiers) opening with the sound of a crying baby. Most of the greeting soldiers have been killed and the greetings died down. Roses wither and the bulbs, you eat but marble remains. Our garden can be reached from the bakery. In the garden grows a huge cedar from Lebanon. The baker came from Barneveld where they’re familiar with the bible. We made do with a miserable little chestnut tree, which fell prematurely to the axe, to be cremated in the little emergency-stove. Mum used to call me out in the middle of the night when they were felling trees in the street and I would have to try pick up the left-overs. - Back, out in the street, I meet another ex neighbour, Mrs. ‘Van Elven’ she’s now in her eighties. She’s sweeping the stoop in front of her place. After a short introduction she recognizes me and calls Mrs. Goorkate.

The family Goorkate had ten children. Her husband used to lend me holy books, such as the life of Gemma and the Pastor van Ars who ate mildewed potatoes out of a net hanging on the wall. He, with the aid of magic produced an attic full of grain. Something that never happened with us.

* * * * * * *

Petite histoire

1940 – 1945

In ‘Oorlog en Vrede’ van Tolstoi wordt het verslag van de sergeant over de strijd binnen een kwartier na het gebeuren gekleurd door onwaarheid. Van m’n tiende tot m’n vijftiende heb ik in een wereld van de meest grove leugens geleefd. De leugen is sindsdien niet opgehouden en we ervaren dat als normaal, in de media en in onszelf, zodat we niet, of nauwelijks, meer weten wat waar is en niet waar. Het minst in onszelf.

‘In negentiendriezeven dan zal je wat beleven, dan komt de Jamboree in Nederland’. In dat jaar hielp mijn oom, de NSB'er, Duitsers in padvindersuniform aan een Indian-motor-met-zijspan. Zij ruilden hun Duitse fietsen in en mijn broer Theo ruilde zijn degelijke Hollandse fiets weer in tegen zo’n Duits model. Het bleek een slechte ruil.

Die NSB-oom was zetbaas in een motorenzaak op de hoek van de Middenweg en de Ringdijk. Een enkele keer mocht ik daar bij oom en tante logeren en reed dan mee in de zijspan van de Indian die eruit zag als een Harley-Davidson, maar dan rood met een Indianenkop aan weerszijden van de tank. Eerst knoopte je het zeildoek rond je vast en dan keek je of bekenden je wel zagen. Het was met mooiste als je dit geluk kon delen. ‘Schele-zie-je-me-niet-ik-rij’ was bij ons de standaarduitdrukking voor dit soort geluk. Oom rolde z’n eigen sigaretten: Zware van de Weduwe, of Ibis-shag. Hoe die ‘goeie’moffen bij die foute oom kwamen weet ik niet. Oom was gek op Duitsland; hij kwam er vaak met m’n dikke tante samen op de motor. Oom was zeer onder de indruk van die nieuwe autowegen die Hitler had aangelegd en daar heeft oom dankbaar gebruik van gemaakt tot aan Rome toe. Rome heeft hem niet veel geholpen, want hij bleef twijfelen tussen Mussert en de kerk, tenslotte werd het Mussert. Dat hij door zijn joodse baas werd ontslagen heeft hem over de schutting getild. Later heeft oom revanche genomen door in het huis van een jood in Badhoevedorp zijn intrek te nemen. Toen was de oorlog al op dreef en werden de joden gedeporteerd. Eén keer zijn mijn jongste zusje Joke en ik vanaf de Westlandgracht naar hun huis in de Amersfoortselaan gelopen en dat was tevens de laatste keer dat we oom hebben gezien. Het verslag dat we thuis uitbrachten, hoe tante pannenkoeken bakte en naar de Duitse piloten opgooide tijdens het draaien deed bij m’n ouders de emmer overlopen. Dat ik tante na de oorlog heb teruggezien en sterker nog bij haar in de kost ben geweest, gaat chronologisch te ver. Ze was in het geheel niet bekeerd en paste goed in de kring van de vrouw van Rost van Tonningen. Regelmatig werden er bijeenkomsten van de kameraden en kameraadskes in haar huis gehouden.

Veel Duitsers hadden we voor de oorlog niet te zien gekregen; er kwam wel eens iemand met rozenkransen aan de deur en er logeerde ook eens een jongetje met Lederhosen in de Heemstedestraat vlak bij fietsenmaker ‘Piet Pelle op zijn Gazelle’, maar helaas is het daarbij niet gebleven. Oom was geen verrader en hij was niet te beroerd om Duitse padvinders naar Amerika te helpen. Na de bevrijding heeft hij trouwens maar even vastgezeten. In gevangenschap zat hij al weer aan de motoren van de Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten te sleutelen en even later aan die van de MP; kort daarop is hij aan longkanker gestorven wat hij bij de Weduwe van Van Nelle en Ibis-shag had opgelopen. Ik kende hem niet anders dan dat hij constant sigaretjes zat te rollen.

Het was een heel enthousiaste tijd, dat proefde je zelfs als kind. Bij ons thuis er intens met de Olympische Spelen van 1936 meegeleefd. M’n oudere zussen legden plakboeken aan van krantenknipsels, foto’s van Rie Mastenbroek en Jesse Owen en er werd gesproken van ónze meisjes en onze jongens’. Mijn vier zusters waren lid van De Graal, van de Maria congregaties, liepen in processies en zongen ‘Gekomen is de lieve Mei, Maria-aaa’. In de kerk stond het in de meimaand vol bloemen; bruidsmeisjes, Jonge Wachters, verkenners tijdens de plechtige opening en de sluiting.

In 1935 waren we van Rotterdam naar Amsterdam verhuisd en woonden we op de Westlandgracht. Hoe m’n zusje Joke en ik het bestonden om op dezelfde gracht te verdwalen zonder die verlaten te hebben, blijft een raadsel. Bij die gracht hield de wereld op. Ik herinner me een grindpad met drollen en een hek met prikkeldraad dat een blijvend litteken in mijn hand heeft achtergelaten. Daarachter lag een brede vaart met aangrenzende tuinderijen van de Mullers, Holla’s, Brockhofs… en daarachter, waar de zon onderging, lag Amerika.

In 1937 kwam de Jamboree naar Nederland. De Schotten droegen rokken, de Zweden kalotjes op hun hoofd, zoals ook de vrienden van m’n zusters die dragen als ze naar Zandvoort rijden op hun blinkende sportfietsen. Zover kwam ik niet en het zou nog minstens tien jaar duren voordat ik daar voor het eerst de zee zou zien. Onze actieradius beperkte zich tot de Hoofdweg, de Baarsjes, het Vondelpark, de Koninginneweg, plus een klein stukje Willemsparkweg, het Stadion en het Schinkelbad. ‘Hoort zegt het voort, dat nu o Nederland niet meer teert op de kracht van een roemrijk geslacht’,…

Achter de Baarsjes, waar ik nooit kwam, werd in 1936 mijn vrouw geboren en we leefden dus al die jaren heel dicht bij elkaar. Niet dat dit voor iemand anders dan mijzelf een opwindende mededeling is.

‘Onze Wilhelmien vierde haar verjaardag op 31 augustus en dan was het, zoals het hoorde, een warme zomerdag met een nimmer aflatende oranjezon en tevens de laatste dag van de zomervakantie.

In 1938 vierde ze haar veertigjarig jubileum. Ik had het voorrecht vanachter de hekken van het huis van bewaring (de gevangenis) op de Amstelveenseweg naar de bonte stoet rijksgenoten te mogen kijken die zich begeleid door de bereden politie naar het Stadion begaf.

Op de Amstelveenseweg stonden een rijtje bomen, en al die bomen waaiden weg, op de Amstelveenseweg – zo luidde een aftelrijmpje.

De paardenmoppen van de politie en de Javanen op hun blote voeten hielden mijn aandacht gevangen. Helaas trapten de Javanen daar niet in.

Ik heb Wilhelmina samen met koning Boudewijn op het Hoofddorpplein in een open rijtuig gezien, maar dat was waarschijnlijk in 1939. Tenslotte kan je als kind niet alles precies weten. Dat ik daar achter die hekken mocht staan – samen met de levenslang gestraften – kwam doordat vader daar in de gevangenis werkte als werkmeester van de kleermakerij.

September 1937 ging ik voor het eerst naar de grote school in de Cornelis Krusemanstraat. Eén jongetje kan ik me nog heel goed voor de geest halen – hij staat trouwens op de klassenfoto in mijn album – hij liep voortdurend te huilen en hij was zo van streek dat hij toen hij uit de WC kwam, vergat zijn piemeltje in z’n broek te stoppen.

De geuren van krijt, stof, urine, ongewassen lijven, duffe boeken zouden nog lang deel van m’n leven uit gaan maken.

Goochem was het niet om het Haarlemmermeerstation als speelterrein uit te kiezen, om daar achter vrachtwagens aan te hangen en tussen de kolenwagons door te kruipen. Eindelijk kreeg ik door dat pa z’n werkkamer uitzag op het terrein van de Oranje Nassau mijn.

Het oog in de kerk had ook iets met het oog van vader te maken: God ziet U! Dat vader daar achter slot en grendel zat, had ik ervaren toen ik naar de dokter moest. Het geluid van sleutels, stalen deuren, de stalen trap die naar de gevangenisdokter leidde, die tevens onze huisarts was, de gevangenen die met maskers door de gangen sloften – ze liepen nog met maskers op om herkenning te voorkomen – blijft me ten eeuwige dage bij. In de Agneskerk tegenover de gevangenis zat God gevangen in het tabernakel. En daar was boven het altaar een oog geschilderd, het allesziende oog van God de vader. Vandaar.

Vader noemde de gevangenis ‘het gebouw’. ‘Ik ben naar het gebouw.’ Zoals een andere vader zei ‘Ik ben naar kantoor’. Het gebouw had alles met het Rijk te maken. Rijksapotheek. Rijkszalf. Jarenlang heeft thuis de foto van vader op de schoorsteenmantel gestaan, in werkmeestersuniform gezeten achter z’n bureau; staalgrijze ogen, grijs haar, scheiding in het midden en een vierkant snorretje dat hij later bij de inval van de Duitsers af zal scheren. Net als God is vader altijd aanwezig; ook als we hem niet zien. Plotseling staat hij er wanneer ik door dat tuindersjong van Holla wordt afgetuigd en vader hem een lel voor z’n kop verkoopt…

Herinnering wordt gauw onwaarheid; het gaat een eigen leiden en het zijn deze gefixeerde portretten die het beeld van een vader opleveren dat permanent wordt. En in de bijbel staat ‘de Vader en ik zijn een’. Zo lijkt het ook met de aardse vader. Laatst schrok ik toen ik zonder bril voor de spiegel stond en het kalend hoofd, die harde, strenge ogen van mijn vader zag. Dáár stond hij… Hendrik… Maar ik was het zelf.

Ik denk dat hij een generatie vertegenwoordigde; je ziet in die tijd overal dezelfde koppen: Colijn, prins Hendrik, Simon Vestdijk. In Duitsland ziet Himmler er ook zo ín en ín fatsoenlijk, zo burgerlijk uit. Hoe moeten hun vrouwen zich gevoeld hebben met zo’n gemillimeterde kop boven zich? Hun echtelijke plicht vervullend tegenover God en vaderland? Nu doe ik of ik over sex in die tijd mee kan praten. Nu dat kan ik niet! Nooit heb ik een blote vader of moeder gezien. Hooguit dat moeder haar tenen zat te knippen; of ze, of waar ze in bad ging weet ik niet. Een douche hadden we niet en toen we naar de Weissenbruchstraat verhuisden heb ik haar daar nooit aangetroffen. Later heb ik zo’n gummibal met bakelieten penis in het gootsteenkastje aangetroffen; ik speelde daar mee zonder me af te vragen waartoe die diende. Het kwam niet in me op het te vragen.

Na die schrikreactie voor die spiegel heb ik geprobeerd vader nogmaals voor de geest te halen.

Da’s gevaarlijk zoals je uit Hamlet weet. Die vader kan op de kantelen van het kasteel verschijnen en je een opdracht geven: ‘Wreek mij! ‘Mijn vrouw, jouw moeder houdt het met je oom, en die heeft gif laten lopen in mijn oor. Hamlet sjachert met die opdracht, maar hij komt er niet onderuit en het toneel ligt op het laatst vol lijken; iedereen is gewroken, de vader… and the rest is silence. Voordat die stilte er is was er heel wat lawaai. En dat moet ook; er moet eerst opruiming gehouden worden.

Ik roep die stilte op om mijn vader te ontmoeten. Radio uit, televisie uit. Ik leg m’n krant weg en het is héél stil in huis. Ik ben een kluizenaar geworden om hem beter te kunnen zien en nog beter te kunnen horen – wat niet vaak voorkwam. Vader was sprakeloos. Als hij sprak, sprak hij in monosyllaben. Doordat moeder ongehinderd toch wel sprak, leek heet of er tussen die twee conversatie plaats vond. Daarmee heeft zij de wereld van pijnlijke stiltes gered. Moeder voerde het woord, tegen hem, voor hem en door hem, en ondanks hem. Denk niet dat ik vol zit van zijn aanwezigheid in mijn jeugd; ik zit vol van zijn áfwezigheid en probeer mij te concentreren op het weinige dat er is. Waar zo weinig woorden weerden gebruikt, maakte hij zich in ieder geval niet schuldig aan vloeken of schelden. Niet één vloek of kreet kan ik me herinneren.

Jaren daarna kom ik op ouderavond: Ú moet meer contact met uw zoontje zoeken.’Ik ben derhalve met hem en z’n vriendje op een dag naar Goirle gefietst. We hebben voor vijftien gulden in een pension geslapen. De volgende dag hebben we ons tentje in de Drunense Duinen opgeslagen en bittere kou geleden. Het was omstreeks Pasen. Ik fietste voorop en de twee jongetjes achter mij. Conversatie was er niet. Ik zie de geschiedenis zich steeds weer herhalen. Wanneer wordt die cirkel doorbroken? Wanneer worden de zonden van de vader niet langer op de kinderen bezocht?

We passeerden de Efteling zonder naar binnen te gaan. Ik vond het te duur.

Vader die hopelijk in de hemel zijt, vergeef mij. Het heeft zo weinig meer met jou te maken. Ik zie dat ik je tutoyeer en dat kwam bij je leven niet in mij op. Als er geen hemel is, besta je niet bij de gratie Gods, maar bij mijn gratie en die van het nageslacht. Ik heb je tien jaar om de veertien dagen in het bejaardenhuis bezocht en ging dan na het ritueel van het pilsje en het sigaartje en het hersenkwellen bij gebrek aan stof met hoofdpijn naar huis. Op weg naar huis zong ik dan vanwege de bevrijding en zei dan tegen Quinten: ‘Waarom zeg je zo weinig; je moet meer met je vader praten! Dat werkt averechts zoals je weet.

Toch hingen we, mijn zuster Ria en ik, aan je lippen voor ieder wijs woord dat er voor je dood nog uit je mond mocht komen. En op je tachtigste verwachtten we nog dat de conversatie van jou uit zou komen. Moeder zat er langzaam dementerend voor spek en bonen bij. Ze werd steeds zachter, vriendelijker en stiller, net zo stil als jij.

Mensen worden geboren en vergaan, de huizen blijven echter wat langer bestaan. Ook die van de joden die naast ons wonen en zondagmorgen vroeg van een feestje thuiskomen in gala. M’n zusje Joke en ik bekijken ze vanuit onze vensterbank op éénhoog als we vanwege de zondagmorgen nog in onze pyjama zitten. We zien de heren met bolhoeden en de dames in het lang uit hun Citroën stappen. ‘Vieze joden’, zeggen we giechelend tegen elkaar. Een paar jaar later staat er in de stad een leuze op de muren gekalkt: ‘Blijf met je gore poten van onze rotjoden af’. Maar dan zijn deze, onze joden, op de Westlandgracht er al niet meer.

1938

In 1938 verhuisden we naar de Weissenbruchstraat nummer 10 en woonden op de bovenste verdieping van een hoekhuis boven ‘Wees niet dom, koop bij Blom’. Ons nieuwe huis had een douchecel zodat we niet langer door onze oudste zussen, Ria of Dora, gewassen hoefden te worden in een teiltje en met een borstel met groene zeep. Als je tenen en voetzolen aan de beurt kwamen schaterde je het uit.

Op een zondagmorgen kreeg ik een bewustzijnservaring die moeilijk valt uit te leggen; ik besefte heel diep het plaatje van het moment, de straat, de ochtendstilte… het besef dat ik deel van de wereld uitmaakte, bestond, woorden die tekortschieten… maar dat het belangrijk was, bewijst dat ik me het heel duidelijk herinner.

Op een keer kwam er ’n vriendje – Disseldorp – het zoontje van de banketbakker op de Koninginneweg bij ons spelen. Die naam Koninginneweg en de Willemsparkweg in het verlengde ervan, hadden een magische klank, daar woonde de haute-volée. Bij de banketbakker hadden ze een dienstmeisje en omdat ik niet voor mijn vriendje wilde onderdoen, wees ik mijn zuster Lice als zodanig aan. Gelukkig zijn we kort daarna verhuisd, zodat het nooit tot een ontmaskering is gekomen. Uiteraard heb ik het nooit verteld.

Omdat we in een hoekhuis woonden keken we ook uit op de Theophile de Bockstraat; op de hoek was de kruidenierswinkel met een manke Duitse dienstmaagd, Martha. Martha trouwde met een communist die haar regelmatig aftuigde. Communist had iets met cellen te maken en met die kerel die op een bankje aan het Jaagpad tegen moeder zei: ‘Mens ga toch niet naar die stomme kerk!’

Bij de winkel van Martha verloor ik onze eerste bonkaart, een suikerkaart; ik had hem toch héél veilig onder m’n bloes gestopt!

Nog zo’n wonderlijke bewustzijnservaring herinner ik mij. ’s Avonds in bed word ik één met het behang. De patronen cirkelen voor mijn ogen en worden steeds dieper als de sterren aan de hemel met steeds meer diepte waarin ik verdwijn. De groep spartelende engeltjes die een wijwaterbakje in hun vlucht dragen hebben daar niets mee van doen, of toch?

Soms wordt het behang steeds donkerder en schrikaanjagender naarmate het patroon zich herhaalt: steeds dezelfde bloemetjes die zich over de naden voortzetten en tenslotte één bloem vormen die langzaam cirkelend zich door de ogen drukt en daarachter een regenboog vormt om daarna sneldraaiend als een klein puntje in mijn hoofd uiteen te spatten; ik roep om m’n moeder die de betovering komt verbreken.

Eerste Communie

God woont in de Agneskerk tegenover de strafgevangenis. Hic domus Deus est staat er boven de ingang. Dit is het huis van God. Hij komt ook in je hartje, daar kan hij ook even blijven wonen. Ik volg dit proces zoals een aardappel in de mond komt en door de ingewanden het lichaam weer verlaat. Ik durf het alleen nooit te vragen. Ik durf bijna niet te denken wat er met die hostie gebeurt. En al die geopende, vieze monden aan de communiebank, met de handen onder het communielaken, uit angst iets aan te raken, te bezoedelen, te morsen… en God moet wél door die speekselmassa, door die ingewanden om te worden tot… ja, durf het maar te noemen, ik niet! Vooraf moet je nuchter blijven vanaf ’s avonds twaalf uur mag je niet eten of drinken. Maar ik heb net voor de Mis begint uit m’n neus gepeuterd en wat moet ik nu, wel of niet te communie? Ik vraag het de meester en ik mag tóch… ‘Heer, ik ben niet waardig dat Gij tot mij komt, maar spreek slechts één woord en mijn ziel zal gezond worden!’ Bul of geen bul. Ja, lach er maar om. Wat een spanning! Hic domus Deus. Wat een eenzaamheid voor Hem als er niets te doen is, geen Mis of Lof. Z’n aanwezigheid kun je aflezen aan een soort seinlamp boven het altaar. Daar zit Hij opgesloten in een gouden tabernakel, zelfs de gevangenen aan de overkant mogen luchten. Een keer per jaar is Hij er niet, op Goede Vrijdag, dan moet hij op paaszaterdag door de spreuken van de priester weer tot leven komen. Dan houd je de adem in en is de hele kerk stil en kijk hoe Hij opgeheven wordt als brood en nog een keer als wijn, maar wij weten beter. Altijd, bijna altijd, zit hij opgesloten in die gouden kooi en kan er niet uit. Hiermee hebben wij ons geloof gematerialiseerd en het opgesloten in een gouden kooi en geen ruimte gegeven en ik denk dat Hij daarom bij zoveel mensen is doodgegaan. Maar dit denk ik pas vele jaren later.

Op straat licht m’n vader z’n hoed bij wijze van groet. De geluiden van de tram naar de remise in de Havenstraat of die Missen van Kuyper die ik nog heb zien dirigeren in de Agnes, een leeuw met grijze manen. Ik weet niet wat God mooier vindt. Nee, ik spot niet, als je dat soms mocht denken. Het gaat verder dan dat.

De slagersjongens zingen ‘rats, kuch en bonen’ als laatste tophit en in de Katholieke Illustratie zie je de parate troepen op de fiets of op de schaats. Het was die winter van ’39-’40 zó koud, dat ik ’s morgens op weg naar school door de Zeilstraat loop te janken. Een flinke Hollandse jongen huilt toch niet?! De mensen spreken van mobilisatie.

10 Mei 1984

In die tijd schreven we de maanden met een hoofdletter. Vandaag is hier alles normaal, is er vrede; toch speciaal deze dag zoals elke tiende mei vertrouw ik niet. Het weer is vandaag niet zo mooi als toen. Menig tiende mei daarna heb ik bijzondere belangstelling voor het weer aan de dag gelegd. Was het weer stralend, dan groeide m’n wantrouwen met de stijging van de temperatuur. Ik kan me de tiende mei van 1941 ook als stralend herinneren. Overal, ook bij ons thuis, waren uit protest de overgordijnen dichtgeschoven. Een straatorgel speelde ‘Hij kan in vrede niet slapen… Hij die zijn leven voor het vaderland gaf. Want daar daar ligt een held die op het Grebbeveld zijn leven voor ’t vaderland gaf.’… Dit zijn flarden van een lied dat me is bijgebleven gezongen op een Duitse melodie. De moffen wisten niet hoe ze het hadden met die vrijwillige verduistering overdag, maar wij wisten des te beter. Zoals vandaag enkelen van ons weten en speurend naar de lucht kijken. Het kan er inééns zijn en dan stopt alles en wordt alles chaos.

Op school was een keuringsarts die me beklopte en in m’n broekje keek en toen mocht ik zes weken naar de vakantiekolonie St. Anthonis in Boxtel. We vertrokken uit de Constantijn Huygenstraat, een zijstraat van de Overtoom. Onze herinnering is als een klerenkast met kielen, boezeroens, overhemden, wollen broekjes, gebreide truitjes, jasjes, jacks, pofbroeken, je eerste lange broek, je gekeerde winterjassen, je misdienaartoog, je schamele ondergoed op stapels, de hemden met rafels, je soldatenuniform van na de oorlog. Daaronder staan de schoentjes, sandaaltjes, kleppers, klompschoenen, klompen en dat ene paar schoenen dat ze gestolen hebben, en dat paar met gaten in de zolen en de schoenen van papier. Na de oorlog wil ik een paar waarvan je de veters zo kan rijgen dat het bovenleer sluit. Schoenen zijn een obsessie geworden. Jezus echter had van alles maar één paar. Dat durf ik niet meer aan. Er moet minstens één paar bij zijn waarmee ik door sneeuw en ijs naar Siberië kan lopen.

Vanaf het Amstelstation rijden we met de trein naar Boxtel. Ik zie voor het eerst van m’n leven bossen die voor de rest van m’n leven hun mysterie behouden, hun omhoogrijzen, hun geur, hun nevel, hun geborgenheid. Midden in die bossen wandelt de witgesteven zuster De Lange. Ik ben ballenjongen op de tennisbaan in april. Er rijdt een cavalerist langs en het geluid van tennisballen op die baan betekent vrede, vooroorlogse vrede en zo zal dat blijven m’n hele leven. Tik, tok, …

De huiskapel zie ik voor me evenals het nieuwe kerkboekje met de plaatjes over wat er op het altaar gebeurt. We bezoeken een kasteel met een slotgracht. Er lopen Augustijnen rond. Een Augustijn vertelt over de andere Augustijn dat hij zo mooi viool speelt, maar dat de man niet in een concertzaal speelt omdat hij daar te zenuwachtig voor is. Ook zo’n plaatje dat permanent in mij aanwezig is. En ik zal dat vaak op mijzelf betrekken. Te zenuwachtig voor het concert van het leven… en toch!?

Gejankt heb ik in die vakantiekolonie van heimwee, voor het eerst van m’n leven en voor het laatst.

Ze laten me janken en ik ga steeds harder blèren, maar het geeft niets. Ik zie wel het hoofd van een zuster voor het raam van de slaapzaal, maar er komt geen redding. Het heeft gelukkig maar een middag geduurd.

Jongens en meisjes die in hun bed piesen, moeten onder de koude douche. Misschien was het water lauw. Koud doet het beter want we dramatiseren het verleden graag. Vele jaren later is er een tentoonstelling over alle vakantiekolonies in Nederland en ik lees vele negatieve reacties van toenmalige kinderen. De mijne is een van de weinige positieve. Ik heb het altijd als weldadig ervaren.

1940

De oorlog kwam als een dief in de nacht. Om zes uur werden we wakker van een ons onbekend lawaai en geratel, gebonk en geknetter. De gordijnen in onze slaapzaal waren op en neer aan het dansen. We werden in bussen geladen die ons terugbrachten naar Amsterdam. Onderweg zagen we Nederlandse militairen met allerlei wapentuig langs de bermen van de weg liggen, lachende gezichten, sommigen met stofbrillen onder hun helmen. Het was schitterend weer. De natuur botte uit als in de Mei van gorter. Overal waren mensen bezig hun ramen met stroken papier te beplakken. Ook thuis waren ze aan het plakken. Aandacht voor mijn thuiskomst was er nauwelijks. Iedereen was in paniek. Er deden geruchten de ronde over Duitse parachutisten verkleed als nonnen of als dienstmeisjes achter kinderwagens. Bij de capitulatie op veertien mei waren er massa’s mensen op straat en iedereen huilde, net als bij het bericht dat Wilhelmina ‘gevlucht’ was.

In de Warmondstraat stond ik me te vergapen aan de intocht der moffen. Ze kwamen over de Aalsmeerweg via het Hoofddorplein de stad binnenrijden, voorafgegaan door een motorordonnans met ’n duivelse helm op z’n kop en een groene camouflagejas. Uit z’n koppel verloor hij een handgranaat die tot mijn verbazing niet ontplofte. Op het trottoir stonden rijen mensen en er waren er zelfs bij die de Hitlergroet brachten. Op een slecht moment zat ik bij een stel SS’ers op de wagen, op hun mouw stond de naam ‘Adolf Hitler’. Ze hadden buitgemaakte, lange Hollandse geweren waarover ze zich tegenover ons vrolijk maakten, want die dingen stamden nog uit de vorige eeuw. Ze smeerden Oberländer met alleen maar jam. Boter kon er niet van af. Kannonen für Butter. Ze deelden onze eigen kwattarepen uit die ze in de plaatselijke winkels kochten. Plotseling werd ik door iemand met een vuurrode kop uit de wagen gesleurd… Het was mijn vader.

Later begreep ik dat deze moffen uit Rotterdam kwamen waar ze hadden deelgenomen aan de gevechten om de Maasbrug. Ik zal de term mof niet vaak meer gebruiken en als die mij ontglipt is het altijd binnen de context van de bezetting. Sommigen menen mij dan te moeten corrigeren. Duitsers zijn een andere generatie, te beginnen bij de mijne.

School

De scholen gingen weer ‘draaien’behalve de onze. Daar liepen de moffen in en uit met koffers en kisten. Een mof bootste een Hollandse vloek na alsof hij de blijde boodschap bracht. Gotvertoeme! Blij waren we met onze betrekkelijke vrijheid van school. Zoals we dat nog vele malen zouden meemaken. Ik heb er een schoolopleiding met gaten aan overgehouden. We deelden na een maand vrijheid het rooster met een andere school op het Hygieaplein en ook onze eigen meester kwam weer uit krijgsgevangenschap terug met een kaalgeschoren hoofd. In september mocht ik wéér naar een vakantiekolonie om de zes weken die boxtel zo abrupt waren afgebroken nu in Dieren vol te maken. Dit soort administratie bleef dwars door alle tumult toch stipt functioneren. Ik ben daar altijd dankbaar voor gebleven. Er werd in mij een ontsnappingsdrang aangekweekt waarvoor ik later toch de tol moest betalen. ‘Er zal wel weer wat gebeuren waardoor die school niet doorgaat.’ En wat je vurig wenst krijg je – werd mij verteld.

Neem me niet kwalijk dat ik van de hak op de tak vlieg, maar der herinneringen komen nu eenmaal niet op bestelling.

Ik zie de eerste zondag van de bezetting bij het standbeeld van koningin Emma bij de Koninginneweg een berg van bloemen aan de voet van het beeld. Er lopen Duitse militairen met een keurige vouw in de lange broek als in een Duitse garnizoensstad. En als op 31 augustus Wilhelmien jarig is, hangen de vlaggen uit in de Zeilstraat. We komen net uit de kerk en de moffen razen met motoren door de straat en schreeuwen dat die Fahnen niet hoch moeten maar naar binnen, alsof dat lapje aan een stok gevaar kan.

Mijn Heer en Mijn God

Ik denk na hoe je als kind voor het eerst met godsdienst in aanraking komt. Voor die eerste herinnering heerst er een heidense onschuld. Je weet niets van God. ‘Zo gij niet wordt als kinderen, zult gij het koninkrijk niet binnengaan!’.. Dat is hoe we de wereld binnenkomen, onschuldig. Enkele jaren blijven we heel dicht bij ons wezen. En dan ineens zie ik een heel donkere kerk in Rotterdam met een zee van kaarsen en heel veel mensen. Die kerk, ‘De Boompjes’, of ‘De Proveniers’ – God zal het weten – is wellicht verdwenen.

Godsdienst? Moeder, die mij als kleuter waarschuwt om geen doktertje te spelen; het spel was nog niet begonnen of het verraad trof mij. De moeder van het bewuste jongetje had donkere ogen, waarmee ze mij nog jaren in mijn dromen boos aanstaart. Moeder spreekt mij boven aan de trap van de Westlandgracht toe over mijn engelbewaarder. Als je engelbewaarder dat ziet… God spreekt door mijn moeder en zwijgt door mijn vader. De romantiek van de flakkerende kaarsen, de bedwelmende wierook, de sinterklaaskledij. Niet past daarbij het roken van de kwajongens op het koor van de Agnes die een kaartje leggen; ook niet het voortdurend gepraat van de jongelui die achter in de kerk staan en bij het Ite Missa est als de donder de kerk uitschieten. De avond voor de inval legt Joep Nicholas de laatste hand aan het mozaïek achter het altaar. De reredos wordt bedekt met stukjes glas die een druivenwingerd gaan vormen. Een klasgenoot woont in de Lohmanstraat, evenals Anton van Duinkerken. God gaat steeds meer buiten je wonen: in de kerk, in het tabernakel, in de hemel. Af en toe in je hartje bij de communie.

Goed Fout

De wereld was nooit zo duidelijk geweest als toen: zíj waren fout en wíj waren goed. Zíj waren gekomen om ons tegen de Engelsen te beschermen. Jaren daarna krijg ik hetzelfde verhaal te horen –

Maar nu ‘straight from the horse’s mouth’, of in duidelijk Nederlands: regelrecht uit de bek van een nazi-hengst.

Ort und Stelle: ein Friedhof – Bad Aussee, Oostenrijk. Een zilveren plaat markeert het graf van een SS-generaal. Ik probeer het schrift te ontcijferen, wat me niet lukt want het zijn Runentekens. Een veertjeshoed van middelbare leeftijd loopt driftig te fotograferen.

‘Das es so was noch gibt!’(ik)

‘Wie meinen Sie?’(mof).

‘Ungeheuer!

‘Sie sind Holländer!

‘Sie raten es!’

‘Ohne Deutschland würden die Engländer euch überschwemmt haben!’

‘Wir haben euch nicht eingeladen!’

‘Eure Wirtschaft konnte nicht ohne uns!’

‘Rotterdam!’

‘Haben die Engländer gemacht!’

‘Die Juden!’

‘Märchen!’

Undsoweiter, undsoweiter, Obergefreiter.

Tijdens ons gesprek had ik m’n wandelspullen in een zak aan een stok over de schouder.

De stok ging steeds heftiger heen en weer. Een stok om een hond mee te slaan.

Dat moet de man hebben begrepen; hij ging met de staart tussen de benen ‘schleunigst’weg. De volgende dag ontmoetten we elkaar weer op straat; hij liep met een grote boog om mij heen. De pret van Oostenrijk was er af; ik wilde meteen naar Frankrijk vluchten want ik zag overal hitlersnorretjes. Tenslotte was dit de bakermat van de nazi’s. (Later lees ik ‘Odessa File’ van Forsyth en wordt mij duidelijk dat uitgerekend het gebied was dat ook Eichmann stiekem na de oorlog vanuit Zuid-Amerika bezocht.) Natuurlijk wilde ik de vakantie voor mijn huisgenoten niet bederven en …. Ging zelfs m’n joodse collega van Het Parool hier niet ieder jaar op vakantie? Die had ook een zilveren plaat, maar als schedeldak omdat daar vroeger een geweerkolf doorheen was gegaan. Op een slechte dag is hij op het toilet achter de zetterij gestorven.

Utrecht